In a search for COVID-19 treatments, researchers pursue a drug used on cats

University of Alberta researchers worked with SLAC X-ray scientists to explore the potential of a feline coronavirus drug that may be effective against SARS-CoV-2.

Researchers at the University of Alberta have shown that a drug used to treat deadly coronavirus infections in cats could potentially be an effective treatment against SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the global coronavirus pandemic. The results were published August 27 in the journal Nature Communications.

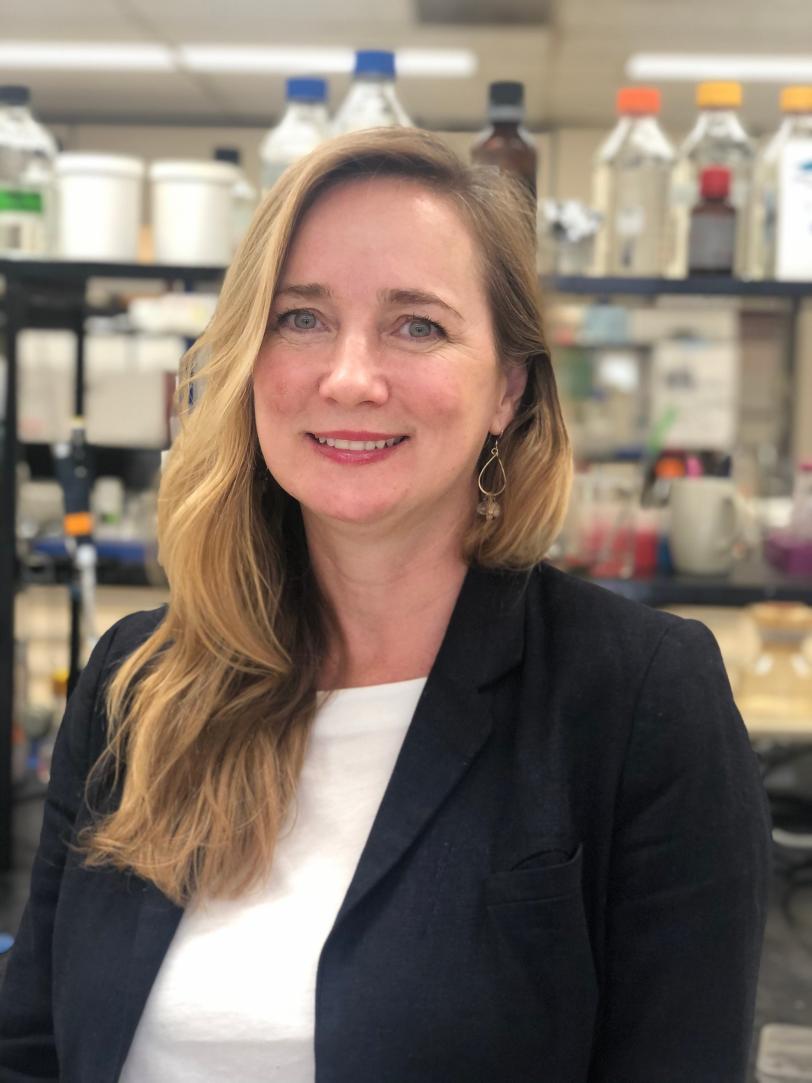

The study, which was aided by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, paves the way for human clinical trials, which should begin soon, said Joanne Lemieux, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Alberta and the study’s senior author.

“This drug is very likely to work in humans, so we’re encouraged that it will be an effective treatment for COVID-19 patients,” Lemieux said, although the clinical trials will need to run their course before anyone can be sure that the drug, a protease inhibitor called GC376, is both safe and effective for treating COVID-19 in humans.

In cats at least, GC376 works by interfering with a virus’ ability to replicate, thus ending an infection. Derivatives of this drug were first studied following the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and it was further developed by veterinary researchers who showed it cures fatal feline affliction.

Lemieux and colleagues at the University of Alberta first tested two variants of the feline drug against SARS-CoV-2 protein in test tubes and with the live virus in human cell lines, then crystallized the drug variants in conjunction with virus proteins. Working with Silvia Russi, a crystallographer and beamline scientist for the Structural Molecular Biology program at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), the researchers determined the orientation of the cat drug as it bound to an active site on a SARS-CoV-2 protein, revealing how it inhibits viral replication.

“This will allow us to develop even more effective drugs,” Lemieux said, and the team will continue to test modifications of the inhibitor to make it an even better fit inside the virus.

Aina Cohen, a SLAC senior scientist and co-division head of Structural Molecular Biology at SSRL, said she was excited by the drug’s effectiveness and by SSRL’s ability to help out. “Until an effective vaccine can be developed and deployed, drugs like these add to our arsenal of COVID-19 treatments,” she said. “We are thrilled to learn of these important results and look forward to learning the outcome of clinical trials.”

The research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. Extraordinary SSRL operations were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Editor’s note: This article is based on a press release from the University of Alberta.

Citation: Wayne Vuong et al., Nature Communications, 27 August 2020 (10.1038/s41467-020-18096-2)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.